In this document, we're going to cover the Linear layer, also called Dense layer, from the theory to an efficient implementation.

In the first place, we're going to cover how a single neuron works, we extend this concept to build fully connected Layer.

01. Theory - Build Fully Connected Layer from scratch¶

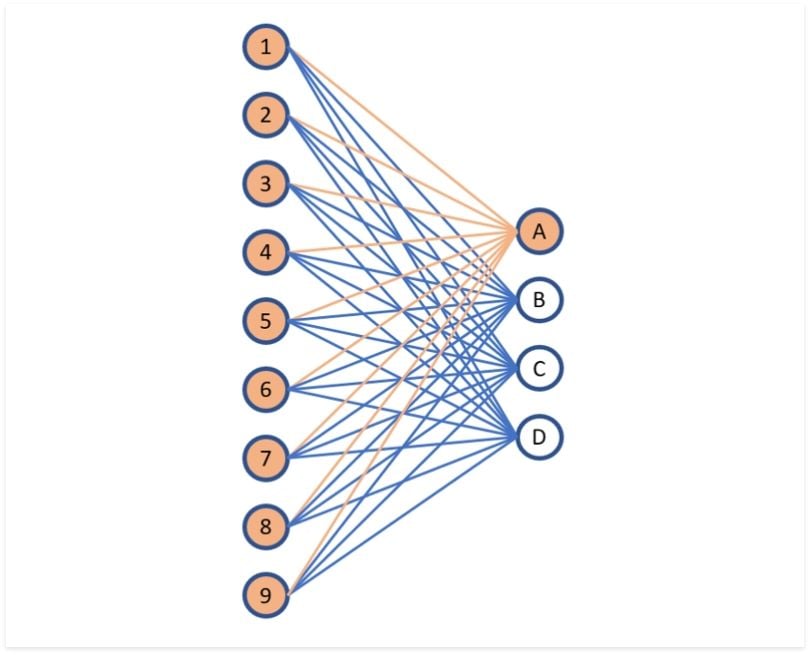

The fully connected layer is a fundamental building block of neural networks. It performs a linear transformation on the input, where each node is fully connected to every node in the previous layer.

To simplify this concept, we'll first explore how a single neuron works. Once we understand this, we can extend the idea to build a fully connected layer.

1.1 Neural Nets - Artificial Neuron¶

The Artificial Neuron is the basic unit used to build more complex neural networks. In this section, we'll delve into the mathematical workings of this neuron.

The Artificial Neuron is a processing unit that takes some given input and produces an output.

Mathematically, it can be described as a function that accepts an input vector $x \in \mathbb{R}^n$ and returns a weighted sum of that input with a weight vector $w \in \mathbb{R}^n$, which has the same dimension as the input $x$, and then adds a bias $b \in \mathbb{R}$, finally returning a scalar output $y \in \mathbb{R}$.

Formally,

$$ \begin{align*} y = w_1 x_1 + w_2 x_2 + \hspace{0.2cm} \dots \hspace{0.2cm} + w_n x_n + b &= \sum_{i = 1}^{n} w_i x_i + b \end{align*} $$

The weight $w_i$ describes the importance of the corresponding feature $x_i$, indicating how much it contributes to computing the output.

The weight vector $w$ and bias $b$ are called learnable parameters, meaning they are learned during the training process.

Acually, we can add the bias $b$ in the weighted sum, by consedering the $w_0 = b$ and set the $x_0 = 1$.

So,

$$ \begin{align*} y &= \sum_{i = 1}^{n} w_i x_i + b = \sum_{i = 1}^{n} w_i x_i + w_0 x_0 = \sum_{i = 0}^{n} w_i x_i \end{align*} $$

There is another way to compute the output $y$ using the dot product of the input vector $x = (1, x_{org}) \in \mathbb{R}^{n+1}$ and the weight vector $w = (b, w_{org}) \in \mathbb{R}^{n+1}$ as follows:

$$ y = w^T x $$

1.2 Fully Connected Layer¶

"In the previous section, we saw how a single artificial neuron operates. Now, we can map the same input vector $x \in \mathbb{R}^{n}$ to multiple neurons and perform the same operation as before. This creates a structure called a Fully Connected Layer, where all output nodes are fully connected to the input nodes."

Note

We will adopt a notation to maintain consistency in writing equations where the weight connecting input node $i$ to output node $j$ is denoted as $w_{ij}$.

Let's start with the first output, considering it as a single neuron performing the same computation as before.

$$ y_{1} = w_{11}x_1 + w_{12}x_2 + w_{13}x_3 + \hspace{0.2cm} \dots \hspace{0.2cm} + w_{1n}x_n + w_{10} = \sum_{i=1}^{n}w_{1i}x_i $$

$$ y_{2} = w_{21}x_1 + w_{22}x_2 + w_{23}x_3 + \hspace{0.2cm} \dots \hspace{0.2cm} + w_{2n}x_n + w_{20} = \sum_{i=1}^{n}w_{2i}x_i $$

$$ y_{m} = w_{m1}x_1 + w_{m2}x_2 + w_{m3}x_3 + \hspace{0.2cm} \dots \hspace{0.2cm} + w_{mn}x_n + w_{m0} = \sum_{i=1}^{n}w_{mi}x_i $$

Beautiful. Let's stack all the equations into a single system of linear equations.

$$ \begin{equation*} \begin{cases} &y_{1} = w_{11}x_1 + w_{12}x_2 + w_{13}x_3 + \dots + w_{1n}x_n + w_{10} \\ &y_{2} = w_{21}x_1 + w_{22}x_2 + w_{23}x_3 + \dots + w_{2n}x_n + w_{20} \\ &\vdots \\ &y_{m} = w_{m1}x_1 + w_{m2}x_2 + w_{m3}x_3 + \dots + w_{mn}x_n + w_{m0} \\ \end{cases} \end{equation*} $$

Hey, does this remind you of something, a pattern here?

Let's turn this system of linear equations into matrix multiplications.

$$ \begin{bmatrix} y_1 \\ y_2 \\ \vdots \\ y_m \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} w_{10} & w_{11} & w_{12} & \dots & w_{1n} \\ w_{20} & w_{21} & w_{22} & \dots & w_{2n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ w_{m0} & w_{m1} & w_{m2} & \dots & w_{mn} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ x_1 \\ x_2 \\ \vdots \\ x_n \end{bmatrix} $$

Thus, we can use the matrix formula to describe the computation of a fully connected layer as:

$$ \begin{align*} \mathbf{y} &= W \mathbf{x} \end{align*} $$

Where

$$ W = \begin{bmatrix} w_{10} & w_{11} & w_{12} & \dots & w_{1n} \\ w_{20} & w_{21} & w_{22} & \dots & w_{2n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ w_{m0} & w_{m1} & w_{m2} & \dots & w_{mn} \end{bmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times (n+1)} $$

Here, $\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^{(n+1)}$ and $\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^{m}$ denote the input and output vectors of the fully connected layer, respectively.

1.4 Forward Propopagation¶

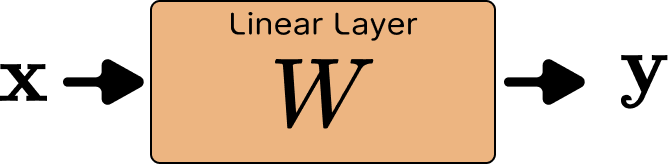

In the previous section, we demonstrated that we could construct a fully connected layer with any number of inputs, denoted as in_features, and produce any number of outputs, denoted as out_features, by constructing a learnable matrix $W$ with dimensions in_features $\times$ out_features.

The forward pass is performed when we compute the output, given a input vector $x \in \mathbb{R}^{(\text{in\_features} + 1)}$ :

$$ \mathbf{y} = W \mathbf{x} $$

1.5 Back-Propagation¶

This is the most exciting part.

The whole point of machine learning is to train algorithms. The process of training involves evaluating a loss function (depending on the specific task), computing the gradients of this loss with respect to the model's parameters $W$, and then using any optimization methods, such as Adam, to train the model.

Let's denote the loss function used to evaluate the model's performance as $L$.

The following figure shows that the fully connected layer receives the gradient flows from the subsequent layer, denoted as $\frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{y}}$. This quantity is used to compute the gradient of the loss with respect to the current layer's parameters $\frac{\partial L}{\partial W}$. Then, it passes the gradient with respect to the input to the previous layers $\frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{x}}$, following the chain rule in backpropagation.

For instance, let's break down each derivative.

The loss function is a scalar value, i.e., $L \in \mathbb{R}$. Let $\mathbf{v}$ be a vector of n-dimensions, i.e., $\mathbf{v} \in \mathbb{R}^n$.

So, the derivative of $L$ with respect to $\mathbf{v}$ is defined as the derivative of $L$ for each component of $\mathbf{v}$. Formally:

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{v}} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial L}{\partial v_1} \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial v_2} \\ \vdots \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial v_n} \end{bmatrix} $$

With the same logic, given a matrix $M \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$, the derivative of $L$ with respect to $M$ is defined as the derivative of $L$ for each component of $M$. Formally:

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial M} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial L}{\partial M_{11}} & \frac{\partial L}{\partial M_{12}} & \cdots & \frac{\partial L}{\partial M_{1n}} \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial M_{21}} & \frac{\partial L}{\partial M_{22}} & \cdots & \frac{\partial L}{\partial M_{2n}} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial M_{m1}} & \frac{\partial L}{\partial M_{m2}} & \cdots & \frac{\partial L}{\partial M_{mn}} \end{bmatrix} $$

1.5.1 Compute $\frac{\partial L}{\partial W}$¶

Since our layer receives the quantity $\frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{y}}$ during back-propagation, our task is to use it to compute the derivative of $L$ with respect to $W$.

Given row index $i \in \{1, ..., n\}$ and column index $j \in \{1, ..., m\}$:

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{ij}} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_1} \underbrace{\frac{\partial y_1}{\partial W_{ij}}}_{=0} + \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_2} \underbrace{\frac{\partial y_2}{\partial W_{ij}}}_{=0} + \dots + \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_i} \frac{\partial y_i}{\partial W_{ij}} + \dots + \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_n} \underbrace{\frac{\partial y_n}{\partial W_{ij}}}_{=0} $$

Thus,

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{ij}} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_i} \frac{\partial y_i}{\partial W_{ij}} $$

We have:

$$ y_i = W_{i1}x_1 + \dots + W_{ij}x_j + \dots + W_{im}x_m $$

Then, the derivative of $y_i$ with respect to $W_{ij}$ is:

$$ \frac{\partial y_i}{\partial W_{ij}} = x_j $$

Finally,

$$ \forall i \in \{1, ..., n \}, j \in \{1, ..., m\} \mid \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{ij}} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_i} x_j $$

Using this formula to fill the matrix $\frac{\partial L}{\partial W}$:

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial W} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{11}} & \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{12}} & \cdots & \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{1n}} \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{21}} & \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{22}} & \cdots & \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{2n}} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{m1}} & \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{m2}} & \cdots & \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{mn}} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_1} x_1 & \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_1} x_2 & \cdots &\frac{\partial L}{\partial y_1} x_n \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_2} x_1 & \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_2} x_2 & \cdots &\frac{\partial L}{\partial y_2} x_n \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_m} x_1 & \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_m} x_2 & \cdots &\frac{\partial L}{\partial y_m} x_n \\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_1} \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_2} \\ \vdots \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_m} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x_1 & x_2 & \dots & x_n \\ \end{bmatrix} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{y}} \mathbf{x}^T $$

Finally,

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial W} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{y}} \mathbf{x}^T $$

1.5.2 Compute $\frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{x}}$¶

With the same logic as before, let's compute the derivative of $L$ with respect to input vector $\mathbf{x}, i.e. $$\frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{x}}$.

For given $i \in {1, ..., n}$

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial x_i} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_1} \underbrace{\frac{\partial y_1}{\partial x_i}}_{W_{j1}} + \dots + \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_j} \underbrace{\frac{\partial y_j}{\partial x_i}}_{W_{ji}} + \dots + \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_m} \underbrace{\frac{\partial y_m}{\partial x_i}}_{W_{jm}} $$

Because we have:

$$ y_j = W_{j1}x_1 + \dots + W_{ji}x_i + \dots + W_{jm}x_m $$

Thus,

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial x_i} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_1}W_{j1} + \dots + \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_j}W_{ji} + \dots + \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_m} W_{jm} $$

Using this formula to fill the vector $\frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{x}}$:

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{x}} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial L}{\partial x_1} \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial x_2} \\ \vdots \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial x_n} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_1}W_{11} + \dots + \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_j}W_{j1} + \dots + \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_m} W_{m1} \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_1}W_{12} + \dots + \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_j}W_{j2} + \dots + \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_m} W_{m2} \\ \vdots \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_1}W_{1n} + \dots + \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_j}W_{jn} + \dots + \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_m} W_{mn} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} W_{11} & W_{21} & \dots & W_{m1} \\ W_{12} & W_{22} & \dots & W_{m2} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ W_{1n} & W_{2n} & \dots & W_{mn} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_1} \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_2} \\ \vdots \\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_m} \end{bmatrix} = W^T \frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{y}} $$

Finally,

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{x}} = W^T \frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{y}} $$

Rules to Compute Gradients

The layer receives the gradient flow $\frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{y}}$. Therefore, the gradients can be computed as follows:

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial W} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{y}} \mathbf{x}^T $$

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{x}} = W^T \frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{y}} $$

02. Implementation - Build Fully Connected Layer from scratch¶

At this stage we've covered all we need to implement the fully connected layer using only Numpy.

For instance, we have two pass modes. First, the forward pass performers of computing the output. Second, the backward pass where the gradients are calculated, helps us update the model's parameters, to make more accurate predictions.